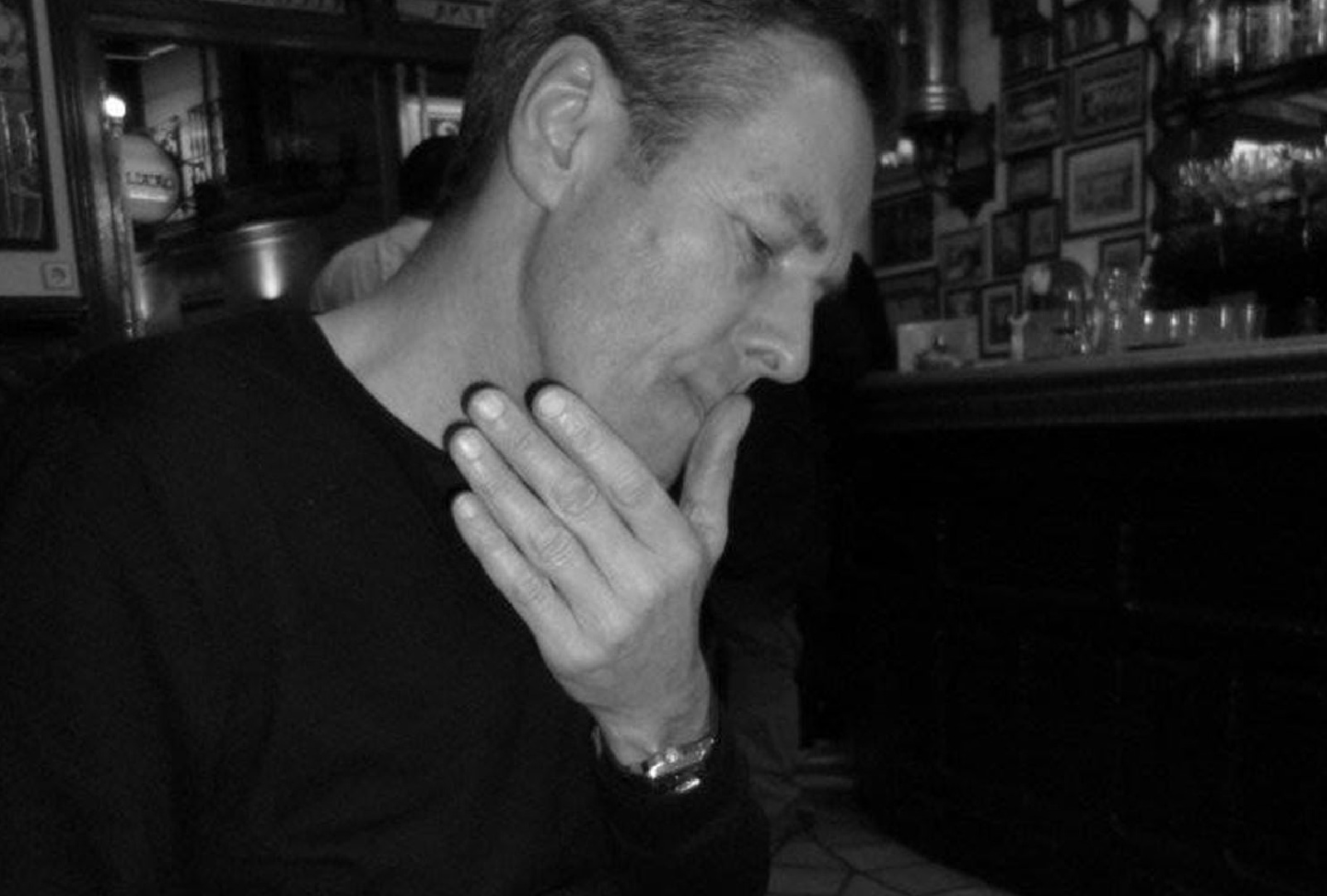

Hussnain

Hanif

IN Conversation

AN INTERVIEW BY HASSAN MAHAMDALLIE

Mohammed Hussnain Hanif, known locally as Hussnain, is a well-respected Nasheed exponent, TV/radio broadcaster and socially engaged arts practitioner of Pakistani working-class heritage who was born and brought up in Brierfield, Lancashire. He has worked with In-Situ and Super Slow Way on a number of projects including Shapes of Water, Sounds of Hope with Suzanne Lacy and is presently collaborating with Super Slow Way and composer and choral director Jules Evans on the Nasheed Choir, fusing Western and Islamic musical traditions.

Shapes of Water, Sounds of Hope 2015 –2017, Pendle. With artist Suzanne lacy and partners In-situ and Building Bridges Pendle.

PHOTOGRAPHER Chris Payne

I meet Hussnain at In-Situ’s base in Brierfield. He is an energetic, friendly man in his late twenties, and when we start to talk, I quickly learn that he is both fiercely driven as an artist and ambitious in his creative vision.

Hussnain combines loyalty to his hometown and the identity it has bestowed upon him, with a broader understanding of his place in the world and his connections to it. This local/global consciousness is, I think, a result of his particular upbringing, being born into a Lancashire working-class family but with its roots in the former empire. “My dad came to this country from Pakistan when he was four years old”, Hussnain tells me, “He’s the youngest of his siblings. His brothers worked in the mills to earn enough money so my father could become the first of his family to go to university. My mum came from Pakistan to England to marry my dad. I'm one of six brothers and sisters. I come from a large extended family – I would say that probably half of the South Asian community living in Brierfield is related to me - so I'm just amongst everybody (I know) here”.

In the same way as his father was “a first”, Hussnain is the first and only one in the family to work in the arts. His journey into the profession differs from the typical middle-class trajectory into the arts facilitated by privilege, money and closed networks. His Muslim culture and belief system has decisively shaped his particular pathway. “I was a Nasheed singer from the age of four” he tells me. “My dad always liked Bollywood songs by popular playback singers such as Mohammed Rafi but he also liked Nasheeds”. Nasheeds are chants or songs with a religious purpose, performed to encourage spirituality in the listener.

“My dad and I would listen to Nasheeds every day, he would teach them to me and we would sing them together. At that age I didn’t understand the languages they were sung in - Arabic, Punjabi, Urdu, Farsi - but I loved the sound of them”.

Hussnain is the first and only one in the family to work in the arts. His journey into the profession differs from the typical middle-class trajectory into the arts facilitated by privilege, money and closed networks. His Muslim culture and belief system has decisively shaped his particular pathway.

Hussnain and his father, and then the local Muslim community, realised he had a special talent for singing. “I started out reciting Nasheeds and performing in the local Brierfield mosque and then further afield, and lo and behold I became this child star. I would be introduced to famous Nasheed artists coming over from Pakistan but I was the only British one, so everyone would come to see how I would sing. That was my early life”.

Hussnain always felt he wanted to do something different, something more, with his singing. “I didn’t want to be purely performing inside the mosque. Yes, my singing comes from a devotional place, from my deen (personal religious conviction), but I always wanted others to enjoy the singing - not necessarily the words, but the melody and how it makes you feel”. As a Muslim of Pakistani descent, Hussnain follows the majority Sunni branch of the religion. His community also recognises Sufism, which is not itself a branch of the religion, but rather a spiritual approach that emphasises traditional ways of Islam and reverence and humility before Allah.

Nasheed Choir rehearsals August 2019, Pendle. With artists Hussnain Hanif and ismaeel hanif.

Photographer Caroline Eccles, Hucklebery Films

Many people believe that Islam is “anti-art” but Hussnain is clear that he draws his creativity directly from his religious heritage. “It is not true that Muslims have no appreciation of art or culture in their everyday lives. In a way the Qu’ran is a work of art: how it’s written, the calligraphy, in the melodies that it’s recited in. Did you know that there are seven different styles or ways of reciting the Qu’ran that take years to learn?”.

However much recognition he received within his community, Hussnain remained alienated from the wider UK arts scene. “When I was younger, I believed ‘art’ was just something for English people until I first went to Pakistan and I found it full of art. For example, if you go into the bazaar you will find very poor woodworkers there making furniture, carving intricate work you would pay thousands for over here”.

When I was younger, I believed ‘art’ was just something for English people until I first went to Pakistan and I found it full of art.

“In Brierfield, a few years back we built a £4.2 million mosque. Everything about the mosque is creative; we carefully selected where we would get our tiles from, the dome has been made by artists, the calligraphy on the walls was drawn by artists, (as were) the decorative Moorish arches, down to the pattern of the carpets. So, now I can see myself as a Muslim whose life revolves around the creative arts”.

In 2010 Hussnain went to Leeds to take a degree in arts, entertainment, and media management. He was convinced his future lay outside of his hometown but a chance encounter made him change his mind. “Before I started my final year, I had decided I wasn’t going to come back to Brierfield but that summer I was walking past Brierfield Library and saw a sign saying there was an ‘art library’ inside. There I met the founding members of In-Situ, the arts organisation that had been set up in 2011. I had been yearning for something like this but thought I could only find it outside Brierfield. I immediately felt part of this family where I wasn’t being judged by my colour, the clothes that I wore or the type of singing I did. They sort of nurtured me in the arts. They were organising arts projects that were tackling social issues in our area. I thought that was fantastic, I was seeing ‘art’ from a different angle and could see myself doing that”.

Nasheed Choir performance, Burnley Mechanics September 2019. With artists Hussnain Hanif and Jules Evans.

Photographer Caroline Eccles, Hucklebery Films

In February 2016, In-Situ and Super Slow Way organised a public meeting in the town’s community centre to introduce everyone to the LA-based artist Suzanne Lacy whom they had invited to Brierfield to explore the possibility of working with her, a town-wide conversation that eventually grew into the project, Shapes of Water, Sounds of Hope. “That initial conversation, I believe, changed Brierfield and the way the community thinks for ever,” recalls Hussnain. “My dad and brothers and sisters were there, and all the prominent members of the community. Up to that point all they knew was that ‘Hussnain had been hanging round with these weird people but we have no idea what he’s doing with them, they may be brainwashing him for all we know!’ But after that night they realised that these people were doing stuff to make our community better. It was a really successful event. Of course, there was a lot of groundwork that had to be done before we could get to that place”.

That initial conversation, I believe, changed Brierfield and the way the community thinks for ever

Hussnain now saw the chance of fulfilling his long-held ambition to develop Nasheeds in a different context, dialoguing with other traditions to reach new audiences. He explains to me that “It’s been my ambition to introduce Nasheed singing as an official art form in the UK and in the West. It’s a highly artistic and creative form. It brings people from different cultures together. It’s reflective poetry that makes you think about life. As a Muslim, I believe any poetry that helps you see yourself better, that works by developing yourself as a person and your community, that talks about world peace and love and harmony - all the things Islam promotes – is perfectly fine”.

“I am British born and bred, I'm very passionate about this country. At the same time, I don't forget that I have an ethnicity - that my origin is Pakistani. And I am a Muslim – there are three identities there. I want to create a form of singing that says all of who I am. The Nasheed Choir, I founded with Super Slow Way and Jules Evans, is exactly that. It’s a fusion of different styles of singing. I didn’t really know what choirs were until I met Jules Evans. Harmony singing isn’t normal in the Middle East or South Asia, we don’t do choral singing - it's group singing or individual singing.

Therefore, I should have my own style of singing – that represents who I am. Pakistanis have been in Britain in numbers for over sixty years – so why have we not also developed our own sound in Nasheeds? The Nasheed Choir is the answer to that question

“Nasheeds are sung across the Muslim world but they also reflect the distinct musical style geographically – the melodies sound different in Arabia than they do in Africa, for example. Therefore, I should have my own style of singing – that represents who I am. Pakistanis have been in Britain in numbers for over sixty years – so why have we not also developed our own sound in Nasheeds? The Nasheed Choir is the answer to that question”.

However, Hussnain has been careful not to undermine the boundaries of his own practice (or that of others) in pursuit of some kind of token hybridity. “I didn’t want to disrespect the Nasheed tradition by mixing it up with contemporary forms, but choral singing is a very classical form of singing. Jules is very accepting of other forms of music and he has fallen in love with Nasheed music. So what we have done is fuse the melodies of South Asia and the Middle East and Africa and put harmonies on them – that has never happened before”.

During the public event at the former Brierfield Mill that was the finale of Shapes of Water, Sounds of Hope, Hussnain and Jules performed a fusion of two songs – one was from Jules - a Shape Note Christian spiritual named Am I Born To Die? - and the other was a song sung at Islamic funerals, that translates as Oh Traveller of This World (your destination is the grave). “The meaning was the same, one coming from Christianity and the other from Islam. We kept the two melodies but crafted them together. It sounded very beautiful and everyone appreciated it”.

“The fusion of these two traditions showed that the commonalities that we share are really important, but that difference is also good. Embracing difference is also part of the Islamic tradition. My job as an artist is to bring people together, to appreciate my music, but it is not about erasing difference. I want to collaborate with people, so long as it doesn’t take away the holiness of what Nasheed singing is originally meant for”.

The Nasheed Choir is an ongoing delicate process. Hussnain explains “to begin with the choir involved just Pakistani boys. There are many reasons for that – but mainly that Pakistani young boys don’t sing; they don’t engage in art”. Hussnain found he had to bring to bear his unique deep understanding of his community as well as his personal reputation, to make it all work. “There is a lot we learnt on the way. For example, I thought it would take a week to recruit to the choir, in reality it took a lot longer. There were lots of intense conversations with parents".

He realised that part of his mission was also to challenge entrenched class barriers that exist in this country: “It was also about building the choir’s confidence to be performers. That’s because working class kids and their families have no engagement with art, they can’t afford the ticket prices and the art on offer has no relation to them. Apart from one, none of the children who sang at Burnley Mechanics in September of last year had ever been in a theatre, let alone performed in one. This was the world’s first ever Nasheed Choir performance. It was a really good night - we were expecting eighty, and 400 people turned up to support the young boys. Older Pakistani women in their 60s and 70s, who wouldn’t dream of going to a theatre, came because Hussnain Hanif – ‘one of us ‘– was working together with non-Muslims interested in Nasheed singing. That brought a smile to their faces.”

Nasheed Choir performance, Burnley Mechanics September 2019. With artists Hussnain Hanif and Jules Evans.

Photographer Caroline Eccles, Hucklebery Films

As our conversation draws to a close, Hussnain begins to reflect on what has been achieved up to now: “People are engaging with us, slowly but surely. In-Situ and Super Slow Way have respect in our community because people know they are very passionate about Brierfield and want to make creative work about our area”.

Hussnain has a message to those arts institutions, funders such as the Arts Council and cultural gatekeepers who wield their power and influence to decide what art forms and traditions are seen as legitimate, who gets to make a living out of the arts and who gets to engage with and benefit from it. “Today, my dad is very supportive of me being an artist - as long as I have another job bringing the money in. Asians won’t come into the arts because of the low pay - there is no money in it. And it’s very hard work. The bigwigs in the arts need to look at this and see how they can make things better and easier for artists to earn a living”.

Hussnain’s vision remains ambitious: “In ten years’ time I want my arts practice to be bigger and better and more diverse. As a British born South Asian Muslim, I want art to be accessible to every single type of Muslim there is. Every single type of non-Muslim there is. For older people, for younger people. I would be very happy if I could have a Muslim-friendly performing arts academy, with students working on their skills, on their confidence, bringing people together, fusing what is positive about our cultures. In our everyday lives we live a hybrid culture – we need to bring that into Britain’s arts practice”.

In ten years’ time I want my arts practice to be bigger and better and more diverse. As a British born South Asian Muslim, I want art to be accessible to every single type of Muslim there is. Every single type of non-Muslim there is. For older people, for younger people.

Renowned Nasheed singer Hussnain Hanif is a Nasheed exponent and TV/radio broadcaster who has performed across the UK and internationally. Nasheed is a westernised form of mid’ha (praise) that originates from the Sufi tradition of Islam and comprises poetic songs of love, harmony and peace. He is currently employed with the BBC and presents 'Thursday Night Takeover' on BBC Radio Lancashire. He co-founded the world's first ever dedicated Nasheed Choir.

Hassan Mahamdallie is a playwright, director and writer. After completing an MA in Theatre Studies at Leeds University in 1984 he worked in Theatre in Education and Community Theatre with companies including M6 (Rochdale) and Pit Prop (Wigan). He is the author of Arts Council England’s Creative Case for Diversity. He was Director of the Muslim Institute and helps edit its journal Critical Muslim. Hassan launched his theatre company Dervish Productions in 2014.

Articles