Super Slow Way: The First 5 Years

Fore

WORD

BY LAURIE PEAKE

Director, Laurie Peake, reflects on the first five years of Super Slow Way and introduces a few of the contributors who will be sharing their own reflections and experiences in this space over the next few weeks.

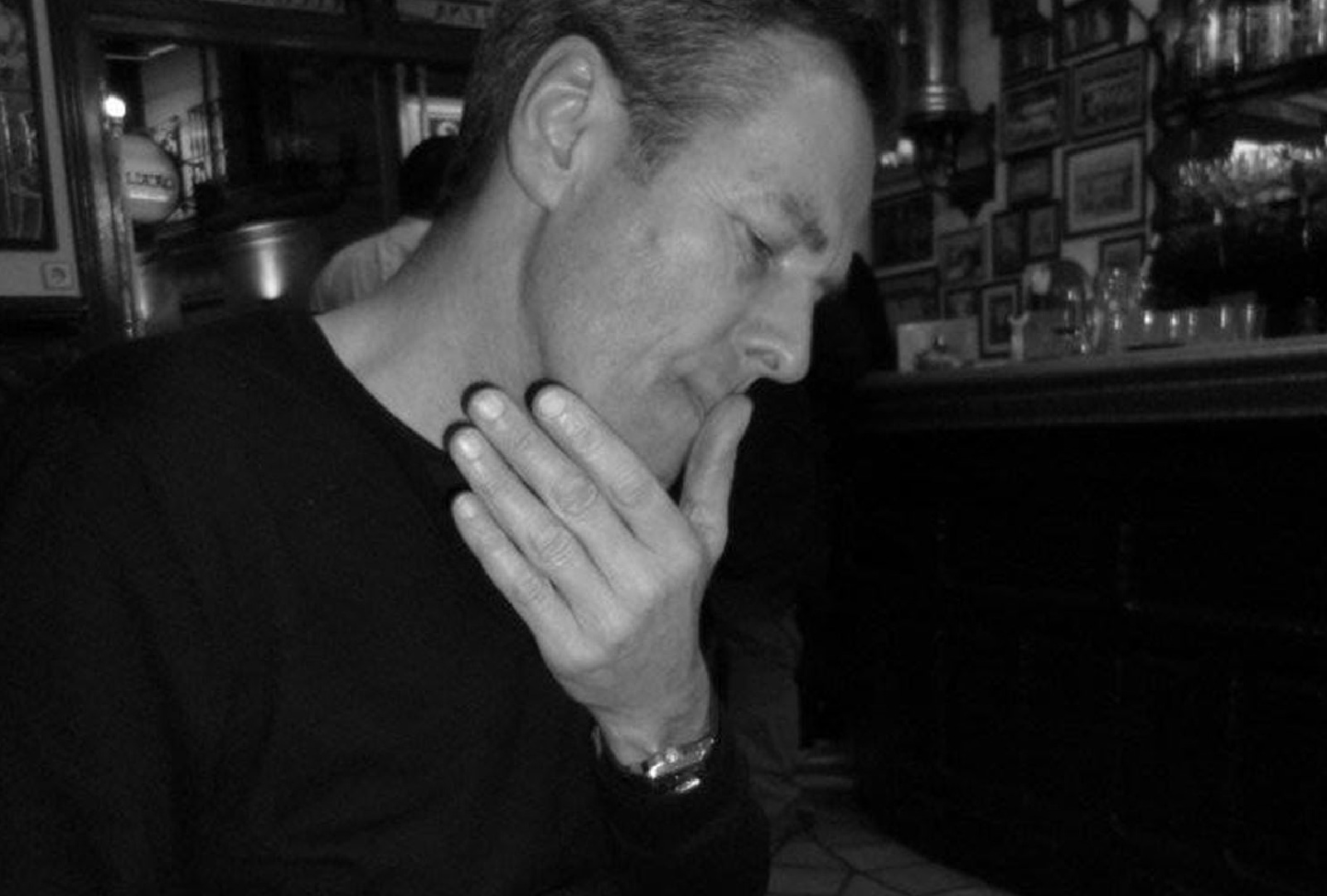

Shapes of Water, Sounds of Hope 2015 –2017, Pendle. With artist Suzanne Lacy and partners In-Situ and Building Bridges Pendle.

Photographer Chris Payne

However, because the train is still rushing forward, people all around you are still talking of acceleration—the increasing pace of change—although in reality the train is no longer going ever faster. Something has changed. Out of the window the landscape is going by less quickly; everything is slowing down. An era is ending”.

Slowdown, Dr Danny Dorling. 2020

I write this in social isolation after a virtual team meeting to plan this publication looking back at our first five years; now, in the shadow of the Coronavirus outbreak, we discussed whether it should influence the content. We have invited a range of our past and current collaborators to reflect on their experience of working with us and many of our contributors are currently rewriting their pieces because this extraordinary crisis is driving them to question their values, their purpose and their practice. Common to all are some positive impulses that seem to be emerging in our first month of lockdown; notably the importance of community and human contact and the value of slowing down and open-endedness, all of which lie at the core of our programme.

Shapes of Water, Sounds of Hope 2015 –2017, Pendle. With artist Suzanne Lacy and partners In-Situ and Building Bridges Pendle.

Photographer Chris Payne

Super Slow Way has, since its inception, sought to hold slowness dear and make time our most precious commodity, inspired by the slow, quiet space the Leeds & Liverpool Canal offers in our fast-paced lives. The metaphor becomes even more powerful and possibly more real at this time, as this waterway, built to oil the engine of capitalism during the industrial revolution and generating the growth of some of the fastest growing towns in the country in the late 19th century, is currently trying to find a new role since the industry it fed has left these places. However, rather than lamenting this turn, Super Slow Way embraces it as an opportunity for the people who live here to explore new forms of personal productivity when they are given time to work with artists, to think differently and find new outlets for action and expression, in collaboration with others.

Super Slow Way has, since its inception, sought to hold slowness dear and make time our most precious commodity,

This publication affords us a moment to look back over our first five years of operation in this context, with a range of collaborators from artists to community members and cultural commentators, to review their experiences and ask what we have learnt together and what art can do and be here. As we wait for the Arts Council decision this week on a further three years’ funding, we will be releasing one article per week in this space over the next couple of months and hope that they provoke and encourage further conversations to shape our thinking about the next three years.

Idle Women 2016, Burnley. With artists Rachel Anderson and Cis O'Boyle

Photographer Dana Popa

From the outset, Super Slow Way has sought to enable artists to offer a space of possibility where people can create new realities and forge new conversations and relationships that would otherwise not exist and to explore what art is to them. As idle women state in their interview, ‘creativity is transformational and art at its most truthful can make profound shifts’. The two producers and activists spent 2016 on the canal here, towing their floating art studio, the Selina Cooper, from town to town, with four successive artists in residence, creating a safe space on the boat and on the towpath with some of the most vulnerable women in the area, many of whom had been captive within four walls for some time before. No project better demonstrates the health benefits that the canal and its green space can provide in these post-industrial places better than their Physic Garden in Nelson where their boat is currently moored, just steps away from where the real Selina Cooper, the inspirational working class suffragist, lived and died, in a neighbourhood of 19th century terraced housing sandwiched between former cotton mills.

From the outset, Super Slow Way has sought to enable artists to offer a space of possibility where people can create new realities and forge new conversations and relationships that would otherwise not exist and to explore what art is to them.

Community Conversation 2020, The Garage Pendle

Photographer Jenny Rutter

A couple of miles further along the canal lies Finsley Gate Wharf in Burnley, an unused wharf and collection of buildings again lying between the terraced housing, former mills and the canal. Stephen Turner’s Egg, an environmental observatory/studio built in timber with a boat builder, sat on the Wharf for a year in 2016. Here Stephen reflects on that year when, almost every day, he would put a kettle on the pot-bellied stove and have tea with all comers, slowly and gently building relationships, making oak leaf ink, sketching and planning all manner of creative activity and events with the local residents who went on to organise those activities themselves. In a neighbourhood where virtually none of the houses have any outside space to speak of, the Wharf became a wildlife centre and a village green where people met and identified themselves as neighbours, often for the first time.

The Exbury Egg 2016, Burnley. With artist Stephen Turner

Photographer Richard Tymon

Similarly, the dye-house at Elmfield Hall in Accrington, a dilapidated stone outbuilding and an unused poly-tunnel, have spawned an endless stream of creative acts with the service users of Community Solutions North West working with artist, Claire Wellesley-Smith, for three years, meeting every Friday without fail. Both of these projects have resulted in the repurposing of our industrial heritage for contemporary cultural expression of the communities that live around them and have attracted investment to save the spaces and sustain their activity. Claire will be reflecting here on that process and the quiet but significant transformations that have arisen from it.

This is social production, carving out social spaces in an area with so few cultural and civic spaces that may be defined as ‘the commons’. Small Bells Ring is a project currently in development with Lancashire Library Service working with artists, Heather and Ivan Morison, to create a floating house of short stories which will moor close to the libraries in Hyndburn whose communities will shape its content and programme alongside writers, aspiring and established. In her piece, Heather discusses the civic role that art can play in society, whether in libraries or on canals, both of which hold the potential of functioning as our cultural commons.

Photographer Claire Wellesley Smith

Artist Suzanne Lacy and Director of Manchester Art Gallery and the Whitworth Alistair Hudson, discuss a similar role for galleries and museums in a conversation that took place in the midst of their planning for Suzanne’s upcoming exhibition across the two galleries. The exhibition will follow her prolific career, promoting dialogue and collaborations with wide-ranging communities across the globe about pressing social issues. The resulting projects often culminate in large-scale, highly choreographed performances as was the case in her residency with In-Situ and residents of Pendle, captured in the film, The Circle & The Square, which will be shown in the exhibition and acquired by the gallery for their collection. Alistair and Suzanne discuss who may own a work created with a community and how social practice can be represented in a museum.

Rauf Bashir, Director of Building Bridges Pendle and Paul Hartley, Director of In-Situ,look back on Suzanne’s three-year residency with them and the challenges and learning it afforded all involved, particularly the legacy of the project, Shapes of Water, Sounds of Hope. Mohammed Hussnain Hanif discusses that legacy from his perspective as a British born South Asian Muslim, with artist and writer, Hassan Mahamdallie, and in particular his desire for ‘art to be accessible to every single type of Muslim there is.’

Focusing on Brierfield Mill, no longer operational but then on the cusp of development, Suzanne and local collaborators worked with residents and former workers to reflect on the role the mill played as a social space where new workers from Pakistan had been welcomed from the 1960s onward and the two cultures met and learnt from each other. The project explored and tested new forms of cultural exchange, ultimately captured in The Circle & The Square that we premiered in the mill during the British Textile Biennial (BTB) in 2017.

Empty mills shape the identity of this landscape just as its residents’ identities are shaped by the industry they symbolise. British Textile Biennial operates against this backdrop, using it as its starting point and its inspiration. As artist in residence for BTB in 2019, Jamie Holman investigated the politics of cloth and his research uncovered trade union banners hand painted on rich silk paraded by Lancashire’s mill workers, leading him to explore mass gatherings and the social, spiritual, cultural and political transformations they generated, from union marches to illegal parties in the empty mills and warehouses abandoned by the cotton industry. Here Jamie reflects on that process and how it has transformed his practice which continues to uncover and celebrate the ‘uncultured’ creativity of the working class in Blackburn.

Live The Dream, Lancashire Encounter Parade 2018, Preston. With artist Jamie Holman and partners Lancashire Encounter.

Photographer Phil West

Banner Culture 2019, Pendle. With partners Mid Pennine Arts as part of British Textile Biennial

It takes time to build relationships, trust and confidence and, when doing this within a group, to find a collective voice where difference and dissonance can become harmonious.

Most of our artist residencies are long-term, rarely less than six months and, in a few cases, three years and ongoing. At a recent meeting, where we invited a group of people who have been involved in a wide range of those residencies over the years to share and examine their experience, time came out as the most valuable tool in their development. It takes time to build relationships, trust and confidence and, when doing this within a group, to find a collective voice where difference and dissonance can become harmonious. This came out as a hugely important outcome right across the board, of equal importance to the chance of creating something of scale and ambition, that again is only possible with the luxury of time while balancing the contradiction of being super and slow. They defined the artistic process as a journey of discovery, not knowing what the product would be or even if there would be an end product and emphasised the importance of this open-ended, self-defined brief that enabled them to go on that journey with the artist and create on their own terms.

As our Critical Friend, Stephen Pritchard notes in his contribution to this developing series of texts,

“It is in the seemingly “little” human relationships and forms – in the new relationships and possibilities and small-scale (but really important) investments made with partners – where Super Slow Way produces social space”

Articles