Suzanne Lacy,

Alistair Hudson

And Laurie PEAKE

In CONVERSATION

This conversation took place at the Whitworth art gallery with Director Alistair Hudson and artist Suzanne Lacy as they planned for Suzanne's show coming to the Whitworth and Manchester Art Gallery in 2021; a presentation of her work across both galleries, developed from an exhibition, We Are Here, first shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in 2019.

AH

What we've been discussing is how you evolve the model of what a retrospective is, particularly with an artist like Suzanne. How do you actually do a retrospective of social practice? I see SFMoMA’s presentation as one version of that and I think we're going to test another version here, in the true spirit of the way Suzanne works, as an activator or activist, so that it's not static but presented as a manual for social change.

We have all these case studies of Suzanne's work through recent decades and we are looking at how we actually use them as an institution within our city frameworks to make projects, make changes happen. We want to pick up the baton of her way of working, with Suzanne's guidance and influence.

Basically the idea is that all shows here at the gallery, each exhibition or presentation of work, contributes to a long term ambition and proclamation, which is about what this institution is, its role in the city, its role in society and how we can use all our resources and networks to make things happen.

SHAPES OF WATER, SOUNDS OF HOPE 2015 –2017, PENDLE. WITH ARTIST SUZANNE LACY AND PARTNERS IN-SITU AND BUILDING BRIDGES PENDLE.

PHOTOGRAPHER GRAHAM KAY

SL

In San Francisco when we began to design the exhibition, the challenge was how do you visualise social practice in a museum—work that took place in very different times and places? From the vantage point of today’s representational strategies, it was hard to even understand what the work was, beyond its original temporal form. The work had been shown in different museums, but each installation actually changed—sometimes a photo, sometimes a video, etc.. The question was, in San Francisco, how do you present performative and social practices in a more permanent, visual manner?

When Alistair invited the exhibition to Manchester, what interested me was his idea about framing the exhibition as a working “manual for change.” This was an opportunity to do what we could not do in San Francisco; to create projects that emanated from the formative ideas in each work, to explore different forms of collaboration and engagement, to activate another set of ownerships in parallel to the historic installation developed so well by the curators in San Francisco (Rudolf Frieling, Lucía Sanromán, and Dominic Willsdon). The Manchester experiments echo strategies that I've used, but also invite new ways of thinking and producing—ones developed by others.

LP

It’s really exciting for Super Slow Way that The Circle and The Square, the film produced at the end of a three-year project that we undertook with you, Suzanne, is one of those works and processes. Even more exciting that the Whitworth is going to acquire the work alongside SFMoMA. That brings up the question of who owns work that's been co-created with the community. How are you responding to that, Alistair?

AH

Well, I think it's a really invigorating development in how you think about collections, for a start. I think one of the things that struck me most about the film was that it was revealing a history and a story of culture that wasn't visible for lots of people, about the history of the textile industry in Lancashire and the history of cultural exchange. It really pulled the rug out from a lot of assumptions people make about cultural exchange and actually shows very clearly how those things really work in all its complexity. It just seemed if we were going to acquire a work of Suzanne's, that it should be this one, given its geographical relevance, but also given the relationship between Manchester, its satellite mill towns and the evolution of culture and commerce in this city. It offers us a perfect opportunity to question how we think about culture and the things we're trying to do now in terms of the modernisation and decolonisation of our collections.

The work speaks in a very interesting way about that and speaks to one of the key things I'm currently pursuing here, which is how you expand the representational role of the museum into an operational one; that’s what we want to do with the show generally. How do you stop the work being just canonized as image and history and how do you make it alive and continue it? I could see that possibility because of the close relationship that we had with you at Super Slow Way, both our relative proximity and the fact that there's a continuum of community that connects us, both as people working with a shared agenda in culture and the ecology of diverse communities that thread together across the north west of England and across to South Asia. I could imagine that this could become a piece of work in the collection that has an active mode of operation in our public programmes and in our future life and work that we're doing in the region around culture, identity, education, youth, voice; all these things. It would become a tool, an agency, a legacy that starts to add complexity to how we think about collections.

SL

Now there is a more sophisticated practice of artists like Tino Seagal or Tania Bruguera attempting to dictate the terms of on-going engagement when a museum collects a work. These experiments in generating future social engagement between cultural institution and community serve as interesting models in changing our way of thinking but have a limited usefulness because institutions often want to create their own engagements and can’t handle the financial burden of on-going programming. What interests me about The Circle and The Square acquisition is your mutual intention of putting the community and the gallery on an equal footing.

AH

Something else we've talked about in the gallery is how do we operate as an institution in this new world we find ourselves in? How do we collect relationships? If we say that art is not merely objects, art is process, which I believe it is, that objects are products of that process which inevitably involves a relationality between things, so how do we, as an institution, collect relationships as we go? This is the challenge we’ve set ourselves and, because this piece was made through a collectivised process, we are acquiring a responsibility but also a set of connections and I think it would be an interesting challenge to develop those relationships as part of the collecting.

SL

Your thinking is so aligned with social practice. I think a lot about not only the individual relationships I’ve formed through work but the way in which collective relationships operate within the communities that produced each project. I go back to places and work again and again with the same people, or connect people between projects. It’s my expanded family. In Manchester I am so excited to be working with Meg Parnell again, after we did an immensely satisfying project at the Manchester Art Gallery in 2015.

THE CIRCLE AND THE SQUARE 2017 PENDLE. WITH ARTIST SUZANNE LACY AND PARTNERS IN-SITU AND BUILDING BRIDGES PENDLE.

PHOTOGRAPHER RICHARD TYMON

AH

Much of the critique around social practice, which I think is well founded, is that often there's a degree of manipulation of people in order to make cultural capital and certainly one of my critiques of participatory work is that it oftentimes involves people participating in a process that's not necessarily something that benefits them. Whereas I think in a situation like this, there's the capacity for this to have continued effect for a wide range of people. It may not be in the same way that it did in the heat of that moment in Brierfield when it was shown but there's something significant about the certification and platform that the museum gives to unheard voices and to an artist like Suzanne who doesn't have commercial representation, who's had to find other ways to operate in the art world.

This exhibition is about giving authority to and supporting and sanctifying that work. The same also goes for cultural identity and representation; when those communities in towns around Manchester have a stake, are listened to and given a voice through the big public institution. I think it suddenly opens up museums to be this amazing agent for people to speak to power that they can't necessarily do on their own. I'm certainly very interested in how these bodies of people, I don't want to call them audience or participants, can understand that you can actually use the art infrastructure, the cultural infrastructure, to speak, to have recourse to power in ways you can't through other channels.

SL

The critique of the manipulation of people for cultural capital is made from the point of view of the art world, privileging their institutions and presuming great financial benefits accruing to artists. What art professionals tend to forget is that (1) social practice art is not terribly “marketable,” and (2) work in communities and among people can actually continue in ways not apparent to us. It doesn't take the artist to point it out; it just goes on in people’s lives and relationships.

There is an interesting example in a project, Skin of Memory, in Medellin, Colombia, with the anthropologist Pilar Riaño-Alcalà. The initial work in 1999 was produced with a broad community of residents, educators, and social activists and took place outside the art world and within national public and non-profit sectors. Eleven years later Bill Kelley, Jr. curated the Medellin Biennial at the Museo Antioquia, and we re-sited the work within the museum itself with our original collaborators. When over seventy-five of our participants and co-creators came to the opening of the installation they were proud and excited to see their work valued in such a place.

It's exactly what you said, Alistair, that the museum gave their efforts, and their barrio itself, credibility and acknowledgement. One of the challenges of social practice art theory is thinking through if and how work goes on; the museum is just one of those places. In the case of The Circle and The Square project, Super Slow Way and In-Situ and Building Bridges Pendle are continuing the efforts they were already doing, ones that came together in the project, in a very robust way that has nothing to do with me.

LP

It will be amazing to see the work here and for the community in Pendle to be close enough to come and see it and like you say, Alistair, to give them agency, to have a place in this institution, to have a voice that has real impact. It would be very difficult not to see it as a catalyst for change within this museum, just to see that gathering of people writ large that are representative of the demographic we have here in the North West which I can't say I've ever seen on the walls of a museum here before.

AH

We have shown more content recently which has had relevance to the South Asian diaspora communities and have begun to build on those relationships. It generates a whole other dynamic when those communities in Manchester start to identify with the potential that an institution like this can have.

SL

I’m excited to see how the combination of leaderships – Alistair with his deep knowledge of social practice, and Laurie, Paul Hartley, Director of In-Situ and Rauf Bashir, Project Manager of Building Bridges and others working so effectively in Pendle—continue the relationship between the community and the visual art world. The work we did together was built on community practices that weren’t mine, the artist’s. I was a catalyst, by generous invitation of people and institutions in the community; they had to agree, to give me permission, to serve in this role.

SHAPES OF WATER, SOUNDS OF HOPE 2015 –2017, PENDLE. WITH ARTIST SUZANNE LACY AND PARTNERS IN-SITU AND BUILDING BRIDGES PENDLE.

PHOTOGRAPHER CHRIS PAYNE

The work we did together was built on community practices that weren’t mine, the artist’s. I was a catalyst, by generous invitation of people and institutions in the community; they had to agree, to give me permission, to serve in this role.

LP

I remember very early on when we first started to talk to people in the town about the possibility of working together to create something with Suzanne and I tried to explain what Suzanne did as an artist to Rauf Bashir and other members of that community, principally the Sufi community of British Muslims predominantly from Pakistan, and having conversations about what is art and what can it be and do? They took a leap of faith with us to co-create something together and none of us knew what it was going to be. They were very brave and worked hard to be understanding and confident of a process that was unknown to all of us but put trust in the relationships we’d formed.

SL

The way that the art world commodifies the artist is super problematic and the artist often falls into this trap. In the beginning people would say that social practices are successful because “look, we did this, this and this.” I could come back to Brierfield and say, “look, they're doing that great Nasheed choir, didn't I do a good job?” Rather than supporting this commodification of the artists great impact, the arts institution has a role in carrying that vision away from the body and the identity of the artist back to the community.

In fact, what happened in Brierfield itself was that the former mill became an art institution; it became the museum for that time, and it did so through the efforts and engagement of many people in that region. That mill as art space built on more than two years of work by In-Situ, who continue to work there culturally, even as the mill is being developed. They saw the space, used it for workshops and exhibitions, and in essence, elevated the site to a cultural one, to affirm that good social practice comes out of the community.

And then you realise that the robustness, the seriousness and the distinguished nature of creating a cultural institution, one that is a shared civic space, is a way in which the community combines to give voice to their own cultural productions. That's essentially what happened with the mill; it had a kind of cultural capital of its own, in a historical sense in terms of labour, but then it was transformed into a contemporary cultural site by agreement of the community. Will they see the Whitworth as an extension of this community cultural site?

LP

It is particularly important in places like Pendle where we're operating, where there is no infrastructure but actually even if there was, it was so much more important to use the mill because residents feel ownership of that place and that space because the majority of them, or their parents or grandparents, had worked there, so to appropriate that space for their cultural expression was paramount and amplified the power of the work.

THE CIRCLE AND THE SQUARE 2017 PENDLE. WITH ARTIST SUZANNE LACY AND PARTNERS IN-SITU AND BUILDING BRIDGES PENDLE.

PHOTOGRAPHER RICHARD TYMON

I'm a great believer that you can’t get people to participate in art unless you participate in what people are already doing. This is a mutual education process.

SL

We are working toward understanding how galleries like the Whitworth can continue the cultural valuing of community production, and how these productions influence the gallery. This isn’t a simplistic task, formally speaking, but requires operating within diverse aesthetic and civic sensibilities. I'm a great believer that you can’t get people to participate in art unless you participate in what people are already doing. This is a mutual education process.

LP

That came over really strong when The Circle & The Square was shown in the Sydney Biennale and a retired policeman from Pendle who was visiting relatives in Sydney came upon it on the day he visited. He didn't even know of the existence of the work or the project and it hit him so powerfully he emailed to say how moved he was by it and thrilled to see his community given a voice on that international platform with such dignity, respect and power.

AH

I think the acquisition of the work continues that process in the museum just as the Nasheed choir and the collaboration between In-Situ and Building Bridges is continuing it in Pendle, creating these moments when everybody comes together. There's just so much investment in the ongoing process, in the visualisation of what's normally invisible.

SL

For me, the question has been how do you operate not just with authenticity, but actually communicate meaningfully in both environments, the community and cultural institutions? For the past few years I’ve been working in a focused way on how to address the “centre” of both community and museum in an environment where the museum exhibition strategies are vastly changing. In the seventies, representation of performance might have sufficed as a grainy black and white video. Today high technology video installations are possible

AH

But also what I like about it is the fact that what we're actually acquiring isn't just the video, we're acquiring the data as well. So, the story is the timeline, the other voices and then that leaves the work slightly more open because you can't necessarily show it the same way all the time. I mean you could but you don't have to. It gives you more to work with to then make it more open as an institution.

THE CIRCLE AND THE SQUARE 2017 PENDLE. WITH ARTIST SUZANNE LACY AND PARTNERS IN-SITU AND BUILDING BRIDGES PENDLE.

PHOTOGRAPHER RICHARD TYMON

SL

How do you show the complexity of sources, histories, relationalities, production strategies when a photograph of people sitting around a table no longer communicates in a museum? What we decided to do in Brierfield, thanks to the collaboration with anthropologist Massimiliano (Mao) Mollona, was to create a resource room with computers to search our archives, a timeline, books, and documentary videos of the project and conversations between key collaborators.

LP

It seems to me we've come full circle because now the work itself, shown in the museum, will help us all question what art can be and what role it can play in society. And, for example, Rauf now sees what we've produced as a really precious and important cultural resource in that community.

AH

Yes, and you can translate that to here as well, the ambition would be that that way of thinking is transferable. So, you could argue that this project, this community of people, community of interest has created this thing that can then generate itself again, creating other communities of interest around different ways of working. And that might be within art but it might be within day to day life, within the social structures of the city or to help explore how, for example, the Muslim community is regarded within the city or how it deals with its own internal issues as well.

I see huge potential in the spirit that this project generated being quite infectious. And that is something that could, through the institution and the institutions that have been involved in it, move forward and evolve and grow in very interesting ways, that are part of daily living, that are part of a continuum between art and life. Yet, the work can still have that sanctity within the museum.

LP

Well, I think I can speak for the community when I say we’re all really looking forward to working with you both to re-present the project here in 2021.

Suzanne Lacy is a visual artist whose prolific career includes performances, video and photographic installation, critical writing and public practices in communities. Lacy’s large-scale projects span the globe, including England, Colombia, Ecuador, Spain, Ireland and the U.S.

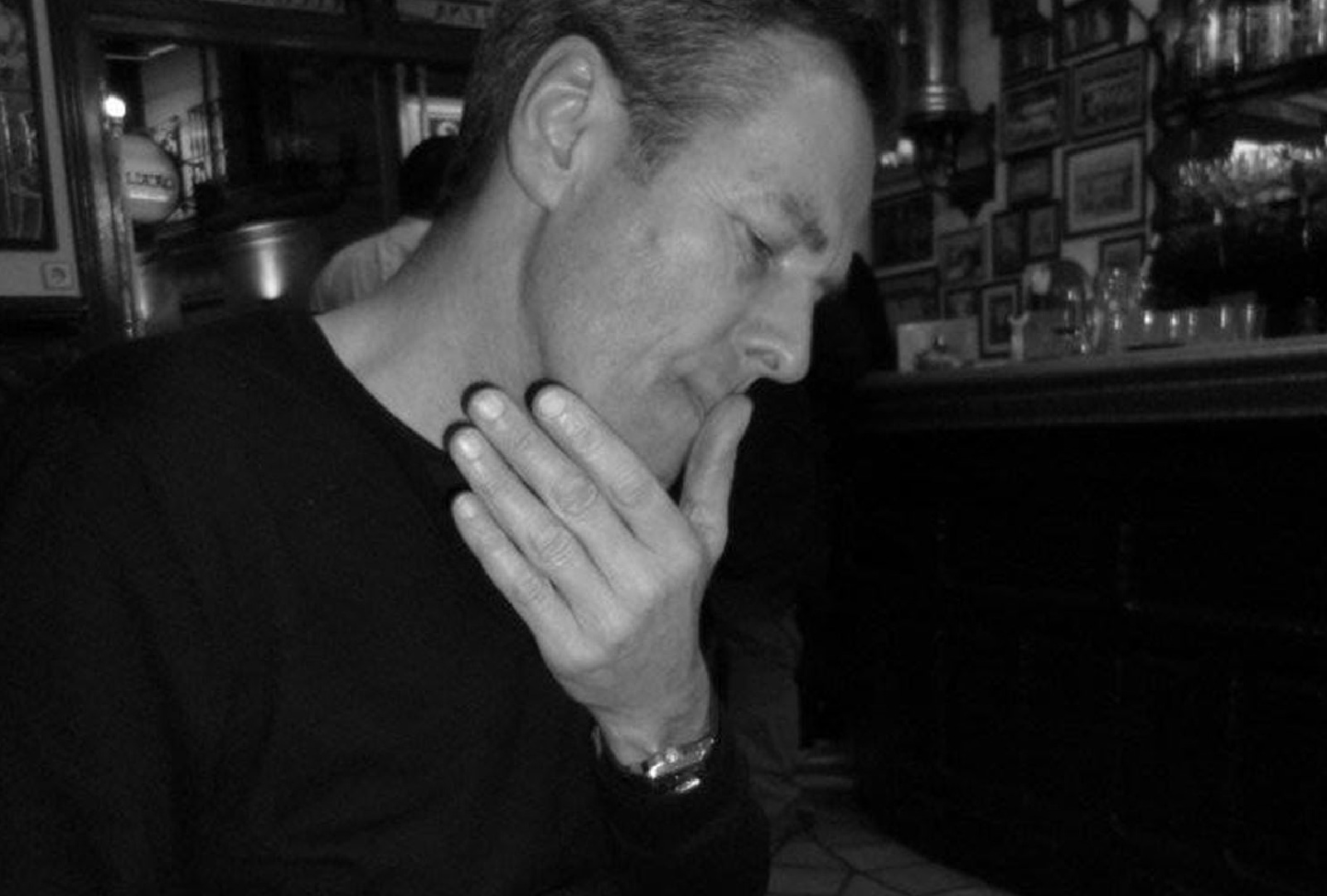

Alistair Hudson is Director of the Whitworth and Manchester Art Gallery, Honorary Professor of Useful Art at the University of Manchester and Co-director of the Asociación de Arte Util. Prior to this Alistair was Director of Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art where he developed the concept of the Useful Museum. In the preceding ten years he was Deputy Director of Grizedale Arts which gained critical acclaim for its radical approaches to working with artists and communities.

Articles